A Visit to the Medical Theatre

Some offbeat thoughts on why we love public displays of affliction.

I indulge in the occasional movie at Nitehawk. What starts as a long walk through Prospect Park leads to a drink at the second-floor bar of the converted Vaudeville theatre. Art Deco detailing and striking windows hint at Nitehawk’s peculiar past - making it the perfect place to watch David Cronenberg’s body horror noir, Crimes of the Future.

The film centers on Saul (Viggo Mortenson), an artist who showcases his body growing novel organs. His “Advanced Evolution Syndrome” performances combine organ production with organ removal, symbolic of the desolate post-pain future he inhabits. Everyone is acquainted with desktop surgery. Elites slice flesh like delicacy with their artisan contraptions. On the streets, littered with cotton candy scraps of asbestos insulation and corroded metal, the poor transform scalpels into budget paint brushes.

National Organ Registry investigators begin logging Saul’s neo-organs. Though responsible for protecting and defining the organic human against a backdrop of escalating body transformations/metamorphosis, they are captivated by his art:

“He takes the rebellion of his own body and seizes control of it. Shapes it, tattoos it, displays it, creates theatre out of it.”

Cronenberg toys with our centuries-long dalliance with surgical theatre. During the Renaissance, public dissections were held several times per year to expose the “secrets of Nature revealed by God.” Anatomists and surgeons highlighted the spectacle with candles and the occasional flutist. Gruesome surgeries turned modern with the application of germ theory and anesthesia in the Victorian era. But some doctors reveled in their showmanship. Scottish surgeon Robert Liston “operated with a knife gripped between his teeth” in the 1800s, more performer than a man of medicine.

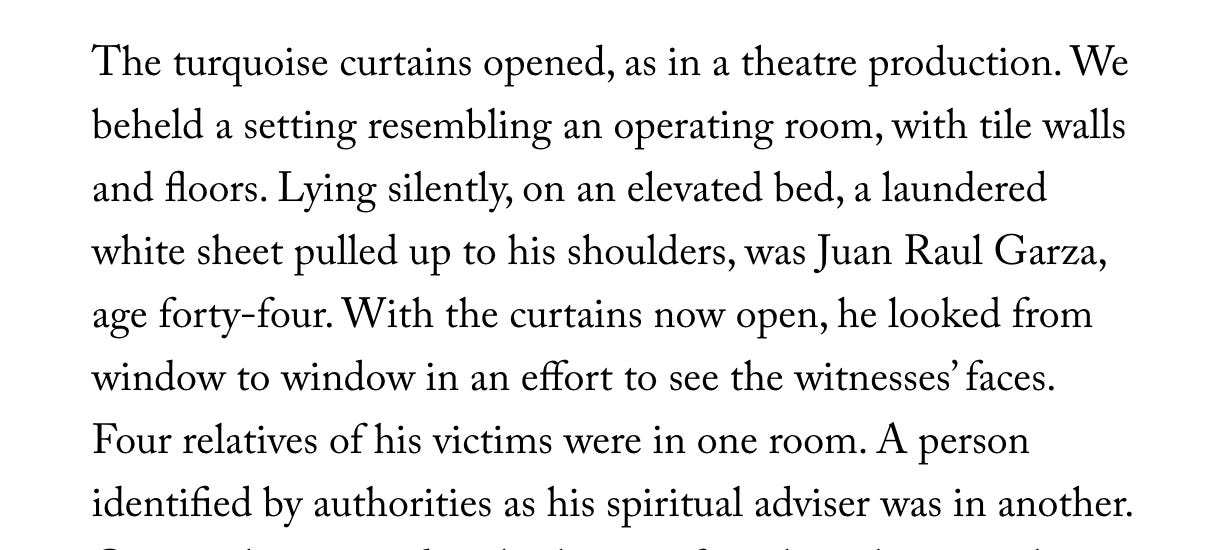

Our morbid fascination with medical technique persists through the death penalty. We replaced the crude and fickle electric chair with a 3-drug lethal injection protocol (a pivot for several drugs like midazolam, an anesthetic commercialized for colonoscopies now in limited distribution for executions). 14 states carried out the death penalty in the last decade, permitting witnesses in the execution chamber:

Cronenberg treats us to a sci-fi upgrade of the surgical bed by fashioning the crustaceous, cybernetic “Sark.” The Sark bed shifts Saul’s body rhythmically to extract his neo-organs during performances. Audiences bear witness and livestream the surgeries with steampunk camcorders. The future seems to stomach voyeurism better than me - I got through these scenes peeking through splayed fingers.

Both the execution chamber and surgical theatre are ceremonial spaces for terrible marvels of innovation. Terrible because this is medicine in strange, brutish form. A marvel because we are captivated by technology and its manipulation of the human body.

Scientists and clinicians invent to limit human suffering. They are craftsmen, tinkering with fantastical elixirs (drugs) and devices. Many of them even experimented on themselves like Saul:

Yes, this kind of self-experimentation is now taboo. Today’s medicine occurs in primarily dull, technical operations, so of course we’re fascinated by the medical spectacle peddled by Cronenberg and gonzo biohackers (exemplified by Dr. Peter Attia and Andrew Huberman).

There’s the approachable, interactive theatre of quantified self (Apple Watch, Whoop, Oura) to YouTube videos of bodybuilders documenting months of peptide use. What of non-convalescent plasma transfusions? Drug delivery nanobots? Startups focused on bioreactor wombs? Fecal microbiome transplants? Neuralink? Now these are leading ladies of surgical theatre. Experimental acts that seize the body as raw material, enframing the body as a technologically modifiable product.

Heidegger wrote that technology reveals the world to us. So we tinker and invest in innovation as spectators of the medical theatre. We wait in exhilaration for these morbid marvels to reveal the secrets of Nature - the possibilities of our dynamic bodies - hoping that one day we may use these technologies to shape, display, and create our own transhuman theatre.

After all:

Errant inspiration and things I thought of while writing this piece:

That one time I tried testosterone

The University of Glasgow’s database of science fiction in the medical humanities

Guinea Pig Zero, a creative zine from the ‘90s written by test subjects of clinical trials

Kushner’s examination of HIV/AIDS in Angels in America (“… a play, if it is to teach its spectator anything, must point at the things one “knows” and ask her to consider them anew. Kushner achieves this by oscillating between keeping the theatrical apparatus in view and encapsulating the spectator entirely in brief but luscious moments of magic. In this way, he avoids the pitfall of Realism, which tends to present events as fixed rather than changeable.”)