Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs) and Biotech Companies as Lifestyle Brands

Been a minute since my last post but I won’t belabor why. Work is challenging (in a fulfilling way) and I’ve started dating again (fun!). My roommates and I are experimenting with new soups and I recently built a yellow couch. I’ve also taken up glassblowing. This sounds like over-egged Brooklyn in your mid-20s so let’s talk healthcare 💉

We miss the infamous Oscar’s slap because we are talking about organ procurement.

I am sipping a tangerine LaCroix concoction in the kitchen, catching up with an old colleague who now works at CMS. Sporadic applause and laughter peter from the living room. We have not seen each other in almost two years, and I learn for the first time that he makes cyberpunk tchotchkes at home with a 3D printer.

On work, we trade wry commentary about government bureaucracy (his team oversees CMS’s product and data-related initiatives). He also shares highlights from migrating CMS onto Jira. “But what’s the weirdest thing that you’re spending time on?” I ask.

He furrows his brows and says after a minute: “OPOs.”

OPOs are organ procurement organizations, responsible for coordinating organ donations between hospitals and transplant centers. I’m informed only 3 of every 1,000 people who die are healthy enough to become organ donors.

“Think about it,” he offers. “A majority of hospital deaths are tied to health complexities like sepsis or cancer. Their organs are potentially deadly to a recipient.”

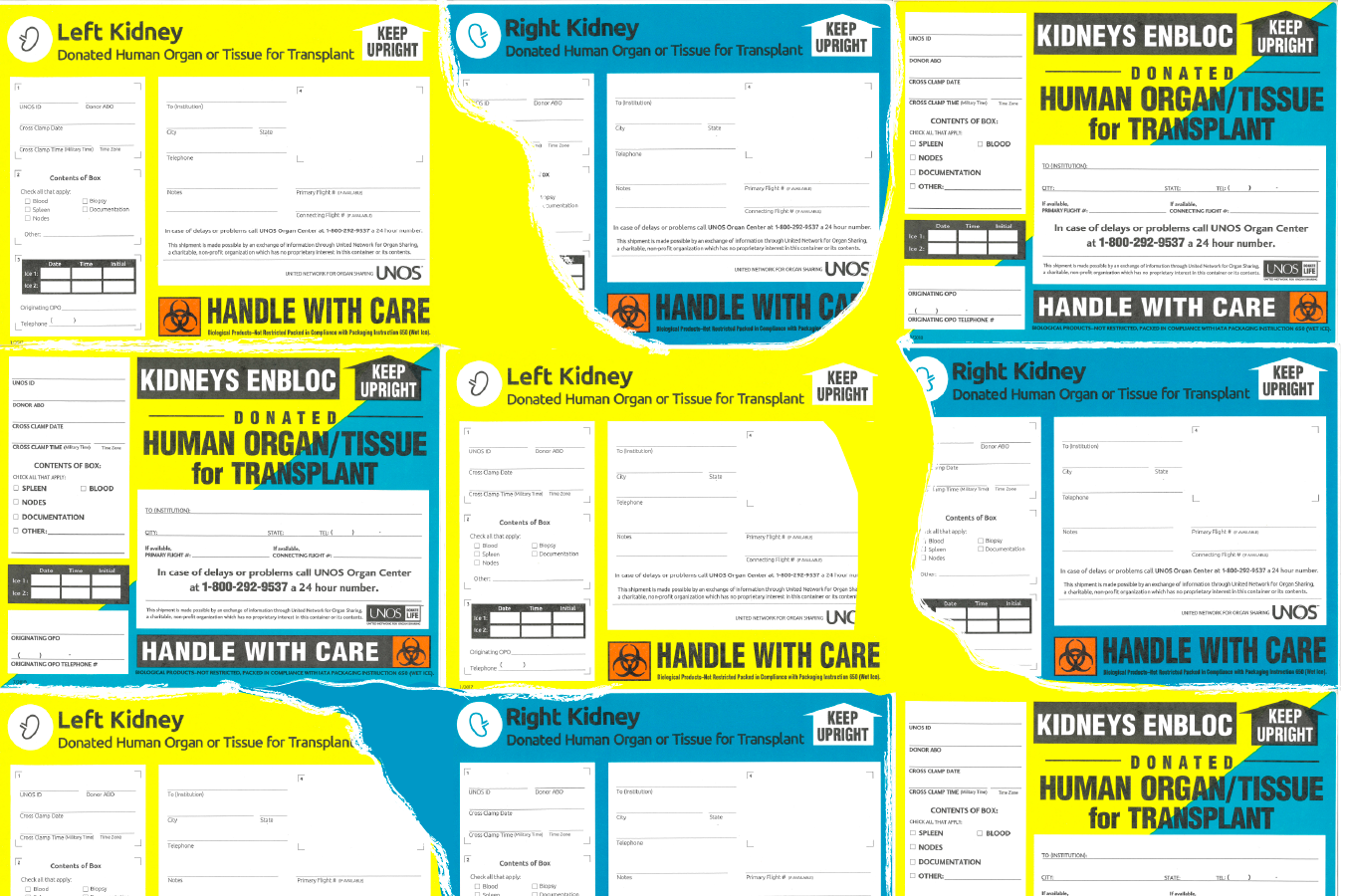

Most transplants are the product of tragedies like comatosis, accidents, overdoses, homicides, and suicides. These organizations work with hospitals to sensitively convince a family that these organs can give someone a second life. Often someone is transitioning off life-supporting treatment; OPO guidelines consider an organ viable for transplant only if removed in the 60 minutes between extubation and death.

Donor specimens will receive a battery of FDA-approved biomarker rapid tests with the occasional specialty lab diagnostic. Eurofins is one company testing cell-free DNA in recipient plasma (% of donor derived-cfDNA strongly correlates with injury/rejection in grafting the transplant).

Then it’s a sprint to match the organs to a national waitlist of ~100K patients.

The National Organ Transplant Act in 1984 established 58 OPOs and saddled each of them with federal contracts to facilitate transplants within 11 geographic regions. My old colleague takes off his tortoiseshell glasses and rubs his eyes between sentences. “The new policies clarify CMS’s authority over creating new OPOs and establishes a system to measure success rates. It’s strange… the same number of OPOs have existed for almost 40 years. None of them have lost federal contracts.”

I assume a position of skepticism towards any cornered market, even if OPOs are charitable 501(c)3s. CMS can require certain governance board structures but does not have the legal power to require full information disclosure, move charitable assets, or make executive leadership changes.

So, until now, OPOs have operated with little scrutiny while managing tens of millions in federal funding. The CEO of OneLegacy in California makes $972,505/yr. Executives from Alabama’s Legacy of Hope were sentenced to federal prison in 2012 for fraud. Alexandra Glazier - the CEO of LifeChoice Donor Services and New England Organ Bank - makes almost $600,000. Her organization charters private jet services and operates a tissue bank; in their 2020 investigation, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform specifically called out “potential impropriety and conflicts arising out of lucrative side businesses, such as a private airline… and tissue banks.”

Weak monitoring also produces alarming donation performance. Studies accuse the U.S. of only capturing one-fifth of current donation potential / missing 30,000 donors a year. Kaiser Health Network has reported damningly on hundreds of organs wastefully mishandled in transit, consequences of “a cobbled-together system of OPOs and couriers and private aircraft and commercial aircrafts.”

Unsurprisingly, a 2019 report found a 400% difference between the top-performing organ procurement organizations and the bottom. Patients without comprehensive OPO support even end up wrongfully billed:

I’m marmalading a cracker as gasps travel through the apartment. Will Smith and Chris Rock have thrown hands (a gross misinterpretation of the slap that will break the Internet). We discuss the new benchmarks that assign OPOs to one of 3 tiers based on regional donation rate (# of donors coordinated from a calculated pool of potential organ donors) and transplant rate.

Third-tier OPOs are at risk for decertification. CMS estimates that 34 of 57 OPOs underperform.

For the first time, decades-old federal contracts will become available for bidding. OPOs are feeling the pressure. 2021 inaugurated the first merger. OPOs also increased lobbying expenditures by 500% according to an investigation from the Project on Government Oversight.

With decertification in effect, the newly available federal contracts tender a rare entrepreneurial opportunity. I often hear someone wisecrack that they should create a hospital startup, exhibiting confidence that their processes and technology implementations would better deliver care.

Well… here’s your chance.

—

In our household, Sundays are ritualistic. It’s either communal cooking or movie night or a bout of intense cleaning. On this particular Sunday, my roommate Kyle, an adventure photographer from Austin, is in his requisite neon running gear with two trash bags in hand. Erin soaks cutlery in the kitchen.

I’m tesselating vials and containers inside our bathroom cabinet. Skincare in translucent glass bottles, spearmint toothpaste, LivingProof styling cream that tended generously to my hair in Berlin, two tubs of Vaseline, makeup (some expired, many untouched).

This is the first time I notice that Erin’s serum and moisturizer come from Biossance. It’s familiar; my mum has Biossance products around her bathroom vanity too. When I’m back on my laptop, scrolling through smallstreetbets (the more palatable sibling subreddit to r/wallstreetbets), I learn that Biossance is the B2C brand of the biotech company Amyris.

B2B infrastructure is all the rage. I hear it from founders, investors, and public market talking heads who are tired of consumer go-to-market. I even work for a startup that is largely considered a “picks and shovels” unicorn for other healthcare companies. But B2B infrastructure - at least, in biotech R&D - is still nascent. Without referencing the cornucopia of instrument and assay suppliers like Sigma Aldrich (Merck) and Thermofisher Science, you have the following:

Ferdi and Juan doing God’s work categorizing the bio stack

I want to zero in on the “end products layer” and rehabilitate direct-to-consumer biotech with Amyris as my case study.

Amyris leverages microbial fermentation, a metabolic pathway where an enzyme acts on a substrate - like yeast - to produce molecules. Amyris claims to sequence and edit genes (the template of enzymes) with proprietary tech, creating new molecules at a higher throughput.

Strain engineering isn’t novel. A jowly cook from the Middle Ages created new microbes by boiling wine purely for the taste far before Pasteur got involved. In the B2B world, Abbvie and Lonza offer bargain prices for microbial bioprocessing. Amyris, too, licenses its fermentation platform to chemical conglomerates. “Precision” fermentation tools might be unique, but the offering hasn’t been enough to unseat most potential buyers from their existing process of developing flavors, fragrances, and drug ingredients.

So the company pivoted its tech in-house to create “clean, sustainable” consumer brands.

With shared services, Amyris has built end-to-end commercial operations for Biossance (skin care), Pipette (baby-friendly products) and Purecane (zero-calorie sugarcane sweetener). They are the engine behind Rose Inc, a beauty brand founded by supermodel Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, and haircare brand JVN, from popular Queer Eye stylist Jonathan Van Ness.

Amyris is a machine that can quickly spin up (and spin down) new brands. Their companies use similar website source code - I checked - and probably share 3PL arrangements for the 15,000 retail stores stocking their brands. Amyris crossed $340 million in revenue last year. Many of the notable B2B companies in biotech make a fraction of that.

Amyris takes after Impossible Foods as a biotech company branding and marketing its unique IP. “Gorpcore” fashion built a cult of personality around novel biomaterial GORE-Tex. Checkerspot seems to be taking a similar approach marketing their ALGALTECH® - “materials [that] fuse biomanufacturing, chemistry, and material science with advanced fabrication to unlock better performance” via alpine gear brand, WNDR.

Gorpcore: the staple clothing palette of hikers and gentrified neighborhoods

When relative quality and switching costs are comparable, B2B solutions become a pricing game. I could reductively frame it as a race to the bottom. We are seeing this dance with companies flitting between different telemedicine staffing APIs, or labs choosing to program mammalian cell lines on 64xBio or Asimov. For B2B solutions to win, they either need to be a top commodity or offer groundbreaking intellectual property (the nice-to-have versus the need-to-have).

In other words, I’m short-term pessimistic and longterm optimistic on B2B.

Biotech companies are in an unusual position to commingle progress with craft and design. It’s short-sighted to undervalue the “end products layer”/B2C strategy when we’re in the consumerization of everything age. Consumers eat, live, wear their values. Is it so crazy to want more biotech companies to cast themselves as lifestyle brands?

Until next time. Opinions my own and do not reflect the views of my employer or any other affiliations.